The desired world travel actually commenced before the career did, as Lofting went straight

to America to begin studies for his engineering degree at the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology. After a year (1904-05) at MIT, it was back to England, to finish up (1906-07) at

the London Polytechnic. Then there followed a brief stint as an architect, after which the

odyssey began in earnest. The newly minted civil engineer did some prospecting and surveying

in Canada in 1908-09, and went on between 1910 and 1912 to work first for the Lagos Railway

in West Africa and then for the Railway of Havana in Cuba. But the attractions of the

life faded sufficiently that by 1912 Hugh Lofting was ready to do something else.

That year, he returned to America, married Flora Small, and settled in New York City to

begin a writing career. HL's entry in the 1931 edition of Living Authors says that the

ex-engineer's first story was about "culverts and a bridge." :-) He soon hit

his stride, however, and was producing short pieces which were published in magazines. Of course,

these stories were different from the books on which his fame would ultimately rest. For one

thing, they were not written for children. Nor did they include any drawings by their author:

Lofting's experience as an illustrator was confined, at this point, to the technical drawing he

had done as an architect and civil engineer.

A new career was not the only thing begun during these first few years of the Loftings'

marriage: they also started a family. Elizabeth Mary was born in 1913; Colin MacMahon followed

in 1915. Meanwhile, Europe went to war, and the Lofting family would not be unaffected.

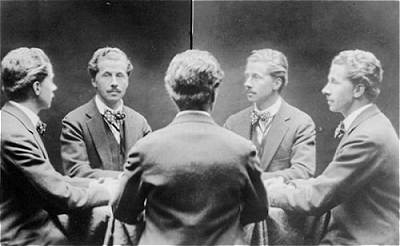

Below:

What appears to be an interesting trick photo of Lofting "times five."

The "Great War" broke out 1914, and in 1915 Hugh Lofting, still a British subject,

worked for the British Ministry of Information while remaining in New York. A year later, though,

he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Irish Guards, and he saw action in Flanders and France

in 1917-18. To say that "the experience affected him profoundly" seems trite and

unnecessary; how could a person of any sensitivity not react deeply to the horrors of war?

And yet out of what was surely a terrible experience came something altogether lovely: the charming

story, told in simply illustrated letters home to Elizabeth and Colin, of an endearingly sensible

little man who values and cares for all creatures as ends in themselves, and who is unsympathetic

only to the falseness and hypocrisy which characterizes much of human society.

It is thought that the idea for The Story of Doctor Dolittle came to Hugh Lofting after

he saw the destruction of regimental horses wounded in battle. In her History of the Newbery

and Caldecott Medals, Irene Smith notes that "[a]t the 1923 conference, after Hugh Lofting

had accepted the second Newbery Medal [for his second Dr. Dolittle book], Mr. R.R. Bowker asked

him how Doctor Dolittle had originated. Lofting said that at the front he had been so impressed by

the behavior of horses and mules under fire that he invented the little doctor to do for them what

was not and could not be done in real life...."

In 1918, Hugh Lofting was badly wounded (struck in the thigh by a piece of shrapnel from a hand

grenade); he would be invalided out of the army before the War's end. His family eventually joined

him in England, and by 1919 they were all ready to return home to New York. The precious Doctor

Dolittle letters had, of course, been saved, and at some stage Lofting began to entertain his wife's

suggestion of turning them into a book. And then, a bit of serendipity:

British poet and novelist Cecil Roberts was on the same ship as the Loftings during their return

trip to America. "Crossing the Atlantic," Roberts later wrote, "I had a neighbor in

my deck chair. Every evening about six he said he had to disappear to read a bedtime story to

Doctor Dolittle. I enquired who Doctor Dolittle might be and he said it was his little son. The next

day a snubnosed boy appeared on deck with his mother and thus I made the acquaintance of the original

Doctor Dolittle. Later Hugh Lofting at my request showed me some of his manuscript and he wondered

if it would make a book. I was at once struck by the quality of the stories and, enthusiastic

about their publication, recommended him to my publisher, Mr. Stokes. I never saw Hugh Lofting again,

but when his first Dolittle book came out, he sent me a copy with a charming inscription."

And so in 1920, a series of letters written to ease the strain of war became The Story of

Doctor Dolittle: Being the History of His Peculiar Life at Home and Astonishing Adventures in

Foreign Parts. Never Before Published ... and an instant children's classic. Readers in both

America and England wanted further adventures, and some youngsters even wrote offering story

suggestions. Lofting seemed happy to comply with the requests for more, and in 1922 he produced

the first of many Dolittle sequels. The Voyages of Doctor Dolittle introduces the character

of Tommy Stubbins, who becomes the Doctor's apprentice and also serves as narrator of the book.

As seen though the boy's wide eyes, our hapless, top-hatted hero becomes a matter-of-factly

self-confident, flute-playing deliverer of dreams-come-true. Voyages is a beautifully

written book, as well as being that rarest of literary phenomena--a sequel worthy of its original.

In 1923, by a vote of the members of the Children's Librarians section of the American Library

Association, The Voyages of Doctor Dolittle won the Newbery Medal (in the second year of

the prestigious prize's existence).

.

After

the War, the Loftings moved to Connecticut. There, Hugh Lofting wrote one Doctor Dolittle book a

year between 1922 and 1928--and other books, besides. He also lectured and gave illustrated talks

to children, whose letters he continued to receive in great numbers (many believed the Doctor to

be a real person). He highly valued those letters, especially the ones he could tell were written

from the child's own impulse, rather than as a school assignment. However, Lofting did not think

of himself as a "children's author," saying later: "I make no claim to be an authority

on writing or illustrating for children. The fact that I have been successful merely means that I

can write and illustrate in my own way. There has always been a tendency to classify children almost

as a distinct species. For years it was a constant source of shock to me to find my writings amongst

'Juveniles.' It does not bother me any more now, but I still feel there should be a category of

'Seniles' to offset the epithet."

After

the War, the Loftings moved to Connecticut. There, Hugh Lofting wrote one Doctor Dolittle book a

year between 1922 and 1928--and other books, besides. He also lectured and gave illustrated talks

to children, whose letters he continued to receive in great numbers (many believed the Doctor to

be a real person). He highly valued those letters, especially the ones he could tell were written

from the child's own impulse, rather than as a school assignment. However, Lofting did not think

of himself as a "children's author," saying later: "I make no claim to be an authority

on writing or illustrating for children. The fact that I have been successful merely means that I

can write and illustrate in my own way. There has always been a tendency to classify children almost

as a distinct species. For years it was a constant source of shock to me to find my writings amongst

'Juveniles.' It does not bother me any more now, but I still feel there should be a category of

'Seniles' to offset the epithet."

Not surprisingly, "Doctor Dolittles"'s family kept pets. At one point there were four

dogs, including one that Lofting and his children chose from that London petshop he had liked to

visit years before, as a boy.

In 1927, Flora Lofting died. Hugh Lofting re-married in 1928, and-- adding loss to loss--

his second wife, Katherine Harrower Peters, became ill and died that same year. In Three Bodley

Head Monographs, Edward Blishen claims that one can see in the Dolittle books of those years a

"deepening of Lofting's pessimism about human affairs." Doctor Dolittle's Garden,

published in 1927, had as a leading character a wasp who described a human battle. And Doctor

Dolittle in the Moon, published in 1928, was intended to finish the series altogether. Popular

demand could not be gainsaid, however, and the hero came back five years later in Doctor Dolittle's

Return.

.

But

happier times were ahead. Lofting was married again in 1935, to Josephine Fricker, a Canadian

woman of German descent. Their son, Christopher Clement, was born in 1936. The family moved to

California, where the author began writing what really would be the last of the Dolittle stories.

Doctor Dolittle and the Secret Lake, written for Christopher, was the work of 12 years

(some of it published, along the way, in the NY Herald-Tribune in a syndicated Doctor

Dolittle feature). The book was completed before Lofting's death, but not published until after.

But

happier times were ahead. Lofting was married again in 1935, to Josephine Fricker, a Canadian

woman of German descent. Their son, Christopher Clement, was born in 1936. The family moved to

California, where the author began writing what really would be the last of the Dolittle stories.

Doctor Dolittle and the Secret Lake, written for Christopher, was the work of 12 years

(some of it published, along the way, in the NY Herald-Tribune in a syndicated Doctor

Dolittle feature). The book was completed before Lofting's death, but not published until after.

Though unable to write at the pace that had characterized his earlier career,

Lofting did produce another published book during this period. In 1941, as the second

"war to end all wars" was raging in Europe, he gave voice to his hard-won pacifism

by composing a "passionate, despairing poem on the recurrence and futility of war in human

history." Victory for the Slain would not be published in the US, however, for by

the end of that year his adopted homeland was at war with Japan, and such a poem was not seen as

suiting the moment. Instead, it was published in Britain in 1942.

Hugh Lofting, whose health had been failing, became very ill during the last two years of his

life, and he died on September 26, 1947, in Topanga, California, at the age of 61. He is buried in

Killingsworth, Connecticut.

[Many thanks to Christopher Lofting for providing the images used above,

and for making corrections to my text.]